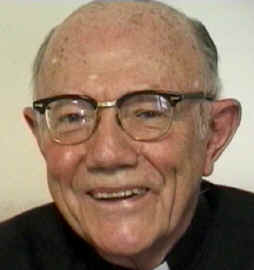

Jim: Today we are visiting Fr. Norris Clarke, one of U.S.’s finest metaphysicians

to find out more about his own life as a philosopher and his thoughts on the possibility

of a creative retrieval of Thomism.

How did you get started in philosophy?

Fr. Clarke: It began really when I was asked to go over and do my philosophy as a young

Jesuit in the Island of Jersey in the English Channel. That was in an entirely French

house. Four of us went over there, the first ones from the New York province to go to

Jersey. When we got there they asked us why we had come there. We said, well we were told

we were supposed to be studying classics, and we were told to come to study under the

famous Fr. So-and-So, a famous expert in classics. So they looked at each other, and said

he has been dead 25 years, which meant we were not up on developments exactly in our

province overseas. So we happily dropped classics and went into philosophy, and it was a

wonderful international house with a wonderful faculty. I had Fr. André Marc who was a

brilliant young Thomist metaphysician, fairly young, and a powerful mind. He took us and

led us through the very beginning, making a judgment, all the way through the entire

development of metaphysics, just unfolding like peeling an onion, so to speak – all

the richness contained at the beginning. It was a wonderful experience. My mind just

opened and blossomed like a flower under that tremendous experience. So that, together

with reading two books, which gave me my sea legs as a philosopher. One of them was

Marechal’s great Plan de depart de la metaphysique, Point of Departure of

Metaphysics, five volumes – in four volumes then – history of philosophy from

the point of view of Thomism, and then ending up finally, well, it was all the way up to,

I guess, Hegel, but St. Thomas was the central focus, and the famous fifth cahier was his

own exposition of St. Thomas, following somewhat the Kantian method of the transcendental

analysis of the conditions of knowing. The entire history of philosophy from the central

point of view of Thomistic metaphysics, that was an extraordinary experience.

I have since not been exactly a card-carrying member of the transcendental Thomist

school for various reasons, but the central thing was the dynamism of the human spirit,

and then the central Thomistic viewpoint. I sat down and read all the four volumes

published then, and made notes on them. That was a tremendous experience of

self-education, along with my Thomist teachers there.

The second book, which was a contraband book at the time, was Maurice Blondel’s L’Action

1893 version. It was a powerful dynamic one, taking what Marechal did with the dynamism of

the human intelligence, Blondel did with the dynamism of the will. If you will anything,

you are committed to will all the way implicitly the infinite good, God, and you

can’t not will because not to will is already to will not to will, so we are

committed. You can’t help not willing. It’s too late. You are thrown into the

world of reality. At that time it was strongly being attacked by Fr. Garrigou-Lagrange,

the great watchdog of orthodoxy, the Dominican, and he claimed it was dangerous,

anti-intellectual, and was under a cloud and should be banned and that sort of thing, so

Blondel who was very devoted to the church said he would do a re-edition, and he

wouldn’t allow a republication of that book until he had done the revision which took

place 20 years later and was not nearly as good. But I got the original. But it was

banned, considered not safe reading for the young Jesuits, so it was banned. There was no

xeroxing things in those days, so a group of scholastics had typed it out in Paris, typed

out that whole book, and then brought it back secretly as contraband. When you were

accepted into the club of real philosophers in the third or fourth year, they would lend

it to you for two weeks. You had to hide it under your mattress because the minister was

very fussy, and would go around checking, did you have any prohibited books? So I had it

for two weeks. I put it under my mattress and read it with tremendous – to will

anything is implicitly to go all the way to willing the infinite. Now that set me up. The

dynamism of the mind and the dynamism of the will in this structure, participation. I sort

of felt I had gotten a hold of the basic meaning and structure of the universe. That was

tremendous. So from then on I felt, the end of my third year, that there was still a lot

that I didn’t know, but I felt I was a philosopher now, had my own sea legs, and

could talk to anybody else in the world. There was a lot I didn’t know, sure, but I

was a philosopher and had a viewpoint on the universe. That was a tremendous experience,

so I am very grateful for that. I didn’t pick up all the later things about the

neo-Platonism and even the participation that much, but I did get that basic Thomistic

vision, and the dynamism of intellect and will is underlying all of philosophy and

spirituality and everything, so that was a tremendously rich experience. And the young

French scholastics were so much more educated than ourselves at the same time, they read

so much more, very sophisticated culture they had, so we used to go out together and sit

on the seashore on the Isle of Jersey, we would sit on the rocks by the seashore and read

Homer in Greek, and various other things. You could just hear the sea in Homer, and read

various things, and it was so good talking about their own inner spiritual experience,

very good at talking about deep things. Americans are shy about talking about deep

personal things, but not the French. They have a great gift for doing diaries, so being

able to speak about spiritual and intellectual things fully without any kind of

embarrassment was just wonderful. So my mind expanded then. I became really very good

friends with them, perhaps better than most people back here. So that was a wonderful

period.

Jim: Did you have any early experiences that predisposed you for philosophy?

Fr. Clarke: I loved high places. I would climb any tree that I could find as high as I

could, and then when I got bigger I would climb up the pillars of the George Washington

bridge, as I told you before – 300 feet, and then go over to the other side of the

Hudson and climb up the Palisades to get the highest viewpoint I could find. And

that’s a kind of an archetype, I guess, when you are up high, you can see how

everything fits together – rivers, and things like that, valleys – and it’s

a kind of symbol of seeing how the universe fits together. So to see things from a high

place, to see them coming together in some kind of unity or pattern, and that’s the

model, so I always used to think about being an archetype, but I didn’t have any kind

of systematic.

And then a young Jesuit who went crazy – afterwards he said there was too much

insulin for diabetes – he took a group of us and gave us a tremendous opening to

spiritual things, the doctrine of the mystical body and all that, so I had had an opening

at the beginning of two years at Georgetown. And then my tree-climbing and rock-climbing

expeditions, but that was sort of a practical, physical kind of metaphysics from a high

place, and now I got into the strictly intellectual side of things.

Jim: Tell us about your first article, the one about the neo-Platonic elements in St.

Thomas.

Fr. Clarke: That wasn’t my first article. My first article has never been

reprinted, "What is really real?" That became quite celebrated in a sense

because it was attacking, even in the Thomistic textbooks, the tradition had gotten in, I

think from contamination with Scotism and various other things, that real being was

divided into classes: actual and possible. So the possibles were one branch of real being.

I thought that when I got into the existential Thomism that it was clear to me that it

could not be at all St. Thomas. Only being with an act of existence was real being, and

that possibles were not real being at all. So I wrote this article attacking this big

tradition, and that made quite a stir and upset some people because even many of the

traditional textbooks would have this division, Thomistic textbooks in Latin, by Thomists,

they had this division of real being that didn’t come at all from St. Thomas. It came

later with Scotus and Suarez and people like that, but it had contaminated Thomism. So

that was the famous one, but it was a long one and has never gotten reprinted. Maybe

sometime it might.

But this other one you mentioned is the one I am best known for. That came not when I

was over in the Island of Jersey studying philosophy for the first time, it didn’t

come there. We were into the existential Thomism, but not quite the neo-Platonic and

participation. It was more modern Thomists. But when I got to Louvain to study,

that’s where I discovered, well, one of the reasons was the books were not out yet.

All this burst out in different authors right around the year 1939 without connection with

each other because of the war coming up. Books during the war did not get around. Those

didn’t really get around until after the war. So those books of Fr. Geiger, on

participation in St. Thomas, Cornelio Fabro, an Italian on participation, and De Finance,

those three books were all on the same line, but they just came out around 1939, and got

lost in the war, and only got known afterwards. So I picked up that whole new development

of the neo-Platonic element in St. Thomas, I picked that up in Louvain when I went there

to do my Ph.D. in 1947-49. That’s where I picked that up. It was all moving around

then. So the combination of the existential Thomism of Gilson plus this new development

gave me the full rich St. Thomas, I think. When I was over there in Europe in 1947 it was

in the middle of all the existentialism, Jean Paul Sartre and all that, and the

phenomenology, so I soaked up that existential phenomenology for a couple of months, and

then went into St. Thomas and tried to put it together.

Jim: What brought about the decline of Thomism at the time of the Second Vatican

Council?

Fr. Clarke: It was a rather dramatic change. When I came back in 1950, and then for

about 10 years, Thomism was really what they called the Thomistic triumphalism. That was

the triumphal period. All the American Catholic philosophical, and Thomism was riding high

in the journals, and Gilson was up in Toronto. That was the Thomistic triumphalism. Philip

Gleason from Notre Dame tried to write up some of that history, that they had a great idea

of unifying all of Catholic culture around Thomistic philosophy, all of Catholic culture.

And even in science and sociology, all of that, to make this the great unified thing that

everybody would accept. But shortly after that the idea of one common philosophy, and then

it became a kind of ideology, that needed to preserve the culture. And then instead of

being for its own sake, it became connected. We’ve got to hold onto this to preserve

the unity of culture, and that’s, as they say, turning it into an ideology as a

cultural defense, and that’s always dangerous. What happened was that with all the

bursting out of novelty and the Second Vatican Council and everything, and the general

blowing off of the lid of respect for authority all during the ‘60s and ‘70s,

this notion of an imposed orthodoxy of philosophy, as well as theology, just was too much

for the young people. They didn’t refute St. Thomas. They just quietly moved away

into phenomenology and other things. They never refuted St. Thomas. They simply shifted

their interest and just quietly dropped him. It was partly the fault of the church making

him, not just the Common Doctor, but required for all of philosophy and theology, and

holding onto this. Then you were part of the Catholic culture to identify it with Catholic

culture, and it became a strait-jacket. So the revolt against authority and all that just

made these young people who were throwing over and opening up to the new modern world,

then we should open up to the modern world of philosophy, too. Strangely they never

examined St. Thomas carefully, the new generation. They just moved away. They lost

interest. So they moved into phenomenology which was the principle thing they moved into.

Some Hegel, I guess, but principally phenomenology. So a massive movement of the young

people out of Thomism into these new trends, and against the old textbook orthodoxy of St.

Thomas. That was what happened. It was a rapid decline. But the good thing, since St.

Thomas got lost, along with the ideology and the rigid textbooks and so on, a great deal

got lost.

Jim: What was the impact of the decline of Thomism on Catholic theology?

Fr. Clarke: I think it had a rather dramatic impact on Catholic theology. They are

beginning to realize now. As Michael Novak once said, "All of the great so-called

liberal theologians, who even got into trouble around the time of the Second Vatican

Council, Schillebeecks and all those people, de Lubac and everybody, even though they were

getting into trouble, all those theologians, innovative ones, were all trained in Thomism

earlier. Of those who were not trained in Thomism, it is not clear that we produced any

really great theologians, so the great innovative theologians, even the ones who got into

trouble, were all trained in the old Thomism. And those who were not, who were so-called

liberated from Thomism, it is not clear that we have yet produced any great theologians,

whether orthodox or unorthodox. So there has been a great decline in the strength and

vigor, systematic vigor, of Catholic theology. There are many theologians, they say they

have stayed away from metaphysics as from a leper, to get away from all that, but as a

result, they get very foggy kinds of theories about the Trinity and so on, like a leading

book, Catherine Lacugna’s book on the Trinity. It is otherwise a good book, she got

prizes for it, she is a wonderful woman, a wonderful Catholic scholar, in her book on the

Trinity she warns theologians they must remember all their fundamental concepts are

metaphorical. Now if everything you say about God is metaphorical, there is nothing

literally true any more. You can’t even say that if everything is metaphorical, you

are endlessly chasing because metaphor means it is like something else, and that’s

like something else, and like something else, so you never have a literally true statement

about God, even that God is intelligent, God is wise, God is good. If it is all metaphors,

what is? And how about being? If that is a metaphor that God is, what is it like?

Something else that is not being? So that is an impossible situation. That’s not

thought through clearly. Philosophically, whatever, the orthodoxy of it is just not

thought through. But that can go along. So I think the theology has been seriously

weakened because of a lack of a clear metaphysics. It has been a very serious weakening.

But the remarkable thing is that the creative theologians, even those who got into trouble

and went too far, they were all trained on the old strong Thomism and then they branched

out creatively, but those who were liberated, don’t seem to have gone much of

anywhere except to get all kinds of somewhat fluffy. Now, that’s a bit strong. There

are any number of good theologians, but not the really great theologians, strange to say,

so that the liberation didn’t seem to give them wings to fly that much.

Jim: How can we recover the riches of Thomism today if it is not being taught?

Fr. Clarke: I think what is happening now is that in somewhat of a vacuum of solid

philosophical theory, what is happening is that the Thomistic metaphysics and philosophy

is coming back through the door of ethics. People like Alistair MacIntyre who, as you

know, has become a convert to Catholicism finally and has attacked all the modern analytic

ethics and has put out his own books, and finally one on three ways of doing ethics, Kant

and Aristotle, and where he is opting for St. Thomas as the best way to do it. He went

over two years ago to England to study St. Thomas during the summer with his old classmate

Hubert McCabe, the Blackfriar Dominican, so he studied St. Thomas, and he’s bringing

it back through ethics. So a lot of people are slowly coming to the metaphysics of human

nature and of being through ethics because they see the lack. So I think it is going to be

a slow steady kind of presence. There are young Thomists slowly coming out. It is a steady

presence now, not dying, and slowly getting more perhaps through ethics. That’s how

it is coming back. But it certainly will not be the dominant strain over in Europe. It is

certainly not the dominant strain in the Catholic university, at least in France anyway.

Though in the seminaries it is stronger here. It is about the only place, but it is coming

back slowly through ethics, to be the foundation of ethics.

Jim: How could a creative retrieval of Thomism take place?

Fr. Clarke: St. Thomas, himself, is difficult to get into by yourself because of the

heavy technical armature of terminology that he took over from Aristotle that used to be

coin of the realm for all the Catholic thinkers. It takes about ten years to get really at

home in St. Thomas. What we need now is to have some way of streamlining St. Thomas,

getting his great seminal ideas and putting them across so people can understand them

easily, and see their relevance to their lives without having to go through a whole long

technical training, a whole jargon, as they call it, like Heidegger, who is pretty

impossible, too. St. Thomas isn’t nearly as bad as that. He is much clearer. But what

is needed is to get the rich seminal ideas of St. Thomas out of that technical structure

that is like an armor and get them more easily accessible. That’s what I call

creative retrieval of the thought of St. Thomas, the great seminal ideas. But doing that

upsets some of the Thomistic scholars because it doesn’t seem to know exactly how St.

Thomas was put in it. But I think that’s important. You are taking a risk whenever

you re-express the thought of an older thinker in your own terms, more modern terms, you

are taking a risk, but without that the seed can’t take root in new soil. It is just

restricted to a small group.

For example, when I was teaching out at Santa Clara, I just had a ten-week course on

St. Thomas for undergraduates, and I just hit the great seminal ideas, and these students

were amazed, and they said, "Where has this man been? No one ever gives us any

integrating visions like this. One modern philosopher tells us you can’t know that,

and others say you can’t know this. Nobody tells us what you can know, and no

integrating visions. Where has this man been?" But I didn’t give them all the

technical side. You can streamline it if you really understand something. Great experts on

things have claimed that to really understand any subject you can teach it to a young

person. One man took the challenge of teaching set theory in mathematics to a 12-year-old

boy. They said you can’t do it. He showed how you can do it. To really understand it

you can put it simply, and it can take root. So that’s what needs to be done. It is a

risk to streamline, but I think it is worth it and it’s very important to get those

ideas to take root.

My most recent book, Person and Being, has been republished in the Philippines

with a commentary applying it to ecology, and has been mandated by the Philippine

government as required reading for all Filipino students and higher education studying

philosophical anthropology in order to get them responsible for their environment before

it is too late. But that is precisely that creative retrieval kind of work that some

Thomists have thought was going to not stick into St. Thomas enough, and so on. So I think

the ideas are very fertile, but they have to be put in more streamlined form – just

the great seminal ideas without all the armature. It is dangerous but necessary. People

are doing that all the time with Plato. They have done it for many, many centuries. We

have to do it with St. Thomas, too.

Jim: Are you optimistic about the future of Thomism?

Fr. Clarke: I am moderately optimistic in that, because of its strength, it will be a

steady, steady quiet influence. Many places now are willing to hire one Thomist, to have a

representative Thomist. It won’t be dominant, but I think it will continue as a quiet

thing, and maybe, if the theologians settle down, they might go back to something like

that, but I think of it as a quiet, steady influence. As we get more and more vacuum of

serious thinking in the rest of the culture that there may be such a need to get in a more

solid, rich kind of philosophical backing, it might become more popular again. The Wall

Street Journal just had an astonishing editorial, which you may or may not have seen, that

came out on the moral chaos in the U.S. That kind of vacuum of meaning, and all that, may

really draw people back to something like that, but I don’t look for that

immediately, but a steady, fruitful presence.

Jim: What are some of the areas where Thomism could make a real contribution?

Fr. Clarke: I think one is the philosophy of the person, a powerful notion of the

person as self-possessing, master of one’s dominus sui, self-possessing and

self-communicating and self-transcending, that notion of the person, and then the notion

of an integrating vision of the whole universe as a vast community of beings, all

participating from the source in God, the notion of the universe as a community where

nobody can really be alienated because we are in a community, a kind of connatural

friendship, as St. Thomas says, with all beings. We belong. To be is to belong to a

community for St. Thomas, that notion of instead of being isolated in a meaningless

universe, we are part of a great meaningful community of existence coming from God, that

vision of being as a great unified community and the role of the person in it I think are

very important.

The next area would be in ethics, the natural law of morality, and the third area I

think would be something that is coming up now. There was an article done by somebody who

claimed he was inspired by metaphysics, an article came out in the International

Philosophical Quarterly last September (1996) on St. Thomas’ substantial form and

modern science, showing how the modern science is coming back now to a notion of wholes

which are not just the sum of its parts, but a whole which exercises causal influence on

the parts below it. It is a new thing in science. It was always reductionism. You analyzed

the parts, and the parts influenced the whole, and that’s it, but now there is a

two-way influence: the parts influencing the whole, and the whole as a causal unity

influencing and controlling its parts. Now the notion of the whole as having a causal

force is practically identical with the Thomistic substantial form. So there is a need for

that, called a principle of wholeness, coming back into science – biology, and then

elsewhere. In that area there, which is just sort of beginning, there is an area there for

trying to understand that principle of wholeness in science, which St. Thomas had a notion

of a substantial form which is the act of unity of the whole composite parts in a single

being, especially in biology, but even in atoms and molecules. The whole being a causal

influence. That’s something that got knocked out by the reductionism, the atomism and

reductionism that has been common to science ever since Descartes.

Jim: Tell us about William Carlo and his work on essence and existence and matter

because you are one of the few people who have written about his work.

Fr. Clarke: He was a younger philosopher at that time, and I was the editor then of the

International Philosophical Quarterly, and he got caught profoundly in the existential

Thomism of Gilson. He studied up at Toronto, I believe, and got caught very strongly in

that. The main influence on him was Gerald Phelan up at the Medieval Institute of Toronto

who really went very far in the existential Thomism, and said the language of essence

really doesn’t fit Thomism. It is an older language, so essence is some big solid

kind of a thing with its own density, and then it is put over into existence by the act of

existence, but it has got its own positivity which then is just actualized by existence.

Phelan had said that’s not it at all. That language doesn’t fit, so it is just

the act of existence which then gets limited down, just so it is a much more streamlined

and all out, following out, of the notion that the act of existence is the source and

center of all the perfection in a being. Essence is just the limitation. Phelan saw that

very clearly and gave his famous talk in the American Catholic Philosophical meeting,

putting that forward, that essence was really an older language and really doesn’t

fit the Thomism, and made his astonishing statements that God is Fr. Phelan, but Fr.

Phelan is not God, that extraordinary paradoxical that caused a lot of trouble there

because God is the fullness of existence, and all I am is a limited, so God is all that I

am and much more, but I am not what God is. That was an extraordinary statement, and then

I was one of the commentators on Phelan’s speech, Carlo and myself, so we got

together then, and I was much intrigued by Phelan’s very dramatic kind of

presentation of that radical existentialism, and then Bill Carlo wrote the article which

we published for the International Philosophical Quarterly on that. So he was following it

all the way, streamlining the thing, there is just the act of existence and limited act of

existence.

I felt that he was going a bit far when he said essence is limited just like we are in

frozen water. It is where the ice stops. There is no kind of an extra thing that limits

it. It is just where the thing stops. It is all ice. It is all existence. It just stops at

a certain point. So it is a completely negative kind of a thing. I was a little worried

that that was not giving enough role to essence, but still it seemed to me basically that

any finite being was a limited act of existence, and the whole core of positivity was the

existence. That was a real insight that I used, but it got in trouble with various

Thomists. I know John Whipple and Joseph Owens, all those, they were worried about playing

down the role of essence. They said we have to keep it more as a subject. Otherwise you

are liable to lose potency and various things, so I was a little ambivalent, but I did

write the introduction to his book when he turned his article into a book, and basically

going along with it. Since then I am a little more cautious about doing that for reasons

of potency and so on.

But then the other dramatic application was that once we have taken that any limitation

is just purely negative, there is just existence, and then limited existence, so he

interpreted even matter, which is a lower degree of limitation in St. Thomas, even that as

just a negation of existence – where the ice stops, so to speak, so matter was not

some whole new kind of being, added on, but it was simply the dispersion and imperfection

of existence when it gets dispersed can no longer hold together that much and gets

dispersed over space, so matter would be a purely negative limitation on form and

existence, purely negative. That was really something new. The whole material world, then,

becomes just a kind of negation of the fullness even of formal existence being together

all at once. So that was a very dramatic thing, and I am afraid that Thomists have not

gone along with that. They have been very worried about that. I am a little concerned

about that, that the new level of material being, that kind of limitation, allows all

kinds of new creative expressions of being which didn’t seem to be just negative, so

I am cautious about going that far. I know you go along with him more strongly there, so I

am certainly open to that, but the traditional and very good Thomists have not been

willing to go along. They are reluctant at playing down the essence as subject and so on.

So I am still ambivalent on that, but he had the courage to go follow an insight all the

way to the radical, radical implications of it the way Phelan did, which I thought was

wonderful. I loved that streamlining, but it made me a bit cautious because of the

reactions of others to it.

Jim: Do you think you will do more work on this question of matter?

Fr. Clarke: No, I don’t. It is a very technical kind of thing. The traditional

people have come out rather strongly that we shouldn’t go this way, and to do that I

would have to do a lot more work on the texts. St. Thomas is certainly ambivalent in his

texts. Many texts go for the stronger view of essence, and some don’t. I think there

are other more important battles to fight. It would be interesting to follow that out. I

did it in a European conference for the anniversary of St. Thomas in 1974, a brief one on

essence as limited existence, but it didn’t get much publicity over here. There were

too many other fruitful and rich things that I would like to write on at present rather

than that sort of technical one which wouldn’t have as much implications for a

spiritual life and so on. One of the things that people have been begging me to write on,

younger Thomists – I say, why don’t you write it, but they say, you are

well-known, you could do it – was this doctrine in the natural theology of what used

to be called Molinism, God’s knowledge, so called, of the futurables – middle

knowledge where God would have to know all that you would have done, whatever you would

have done if you had been put in the circumstance, and you may never be put in that. All

that you would have done had God created the world this way, or allowed this to happen

– all the things that you would have done, what would have happened, and then God

said, no, we don’t want that world. But that kind of knowledge of God which was held

by the Jesuits, Molinism, against the Dominican Bañez, because of his tendency towards

too much predetermination. It was brilliant logically, but a good Thomistic metaphysician,

an existential Thomist would look at that middle knowledge as a metaphysical monster. And

it is coming back again through Alvin Plantinga, the Calvinist theologian philosopher,

being picked up by Catholics again in Notre Dame, so-called middle knowledge. And I think

it is a metaphysical monster and a serious misunderstanding for the simple reason that

what you are asking is that God would see what a non-existent will, a decision that a

non-existent will would make. But a decision is an existential something. A non-existent

will can’t make any decisions. If it is true that you would have done this, therefore

God must know it – St. Thomas would have said that there is no truth yet unless there

is being to support it, so I think that is a real metaphysical monster. And it is coming

back again as being a brilliant solution to various things. I don’t think it is a

solution, at all, so I would like to write on that, risking losing some friends, certainly

Alvin Plantinga and in Notre Dame even some of the Catholic philosophers there, reprinting

Molina’s book and all that. We used to have teach that as Jesuits. I refused to do it

when I was put in. And then I discovered the Gregorian University with all the Jesuit

Thomists there had quietly put that knowledge of the futurables, had quietly put that on

the shelf as a historical thesis, no longer systematic, so I was supported then, but I

refused to teach it because no good Thomist could possibly hold that theory, it seems to

me, an existential Thomist. So I would like to write on that because that is making a

difference around.

Jim: Tell us about the work you did on the creative retrieval of an existential sense

of the existence of God.

Fr. Clarke: Well, that was under the stimulus of scientists. I had to deliver that

before scientists, and they were pushing me very hard, and I had never been so challenged.

That’s when it suddenly occurred to me that you couldn’t speak to the scientists

about essence. Essence is a black box for them. They didn’t know what was in there.

So I said, well, what terms do you use? Well, they said, models. So using that term model

it suddenly occurred to them, and then Stephen Hawking in his book had it that suppose you

did get a theory of everything? Everything is explained physically by a simple thing

there. You have got this perfect model of everything. He said, would this model somehow

bring itself into instantiation, this real energy, would it somehow will itself to become

real? The perfect model, but how about the real world? Would it somehow will itself into

existence? What does that mean, or do you need something else? That suddenly hit me, and I

presented that to them. Suppose you got the perfect model? How about getting the

instantiation with energy, real energy? The model is a model for the transformation of

energy, but the model has no energy. That suddenly hit me, and it hit the scientists, too.

Suppose you got the perfect model. Does that mean that many other models that could be?

How about the real instantiation? Some scientists who are sort of nutty, I think, said

that if you could show really that there was only one possible physical universe, you

would dispense with any kind of God, or author or mind, but that is totally to miss it

even if there was just one possible. It doesn’t give you the slightest reason of how

did that possibility become genuinely real with active energy? Just because it is

possible, there is a huge gap between that and the real, and that did impress the

scientists. Hawking amazingly said, how about the model? Is it going to will itself into

instantiation? He lost the philosophical perspective a little bit later in that book, but

still.

Jim: Tell us about your work on person and cosmos.

Fr. Clarke: That’s a somewhat new development that I have been working on in just

the last few years. I have been getting into what is called the new dialogue between

theology and science, and by theology they really mean philosophical theology. It is not

the strict special revealed dogmas. That is a new dialogue going on, and very fruitful

one. Quite different from the old dialogue was theology – keeping science at a

distance. Science is a threat and all that, keeping it at a distance, keeping its own

turf, but theology back in the 16th century after the new science became

strong, theology washed its hands of science and just followed its own path and did its

own, and that was not the way St. Thomas did it at all. So the new dialogue is what we can

positively learn from science, learn about God, the meaning of the universe, it is a whole

new positive dialogue and the Pope in his dramatic letter, which was the preface to that

book you were talking about, said that theology now must, really to be fruitful, must

learn from science and incorporate its findings into it positively. That’s a whole

new positive dialogue, especially about the evolutionary universe. It is not the old fight

about whether or not God is needed along the way. It is not about those partial ones. It

is about a single great story of the universe, a single great story from the big bang on,

and with the human being, however it happened, emerging out of this long story as the

final crown of this long story of development, and being now the divine creativity, not of

a fixed universe, but a tremendously creative universe that grows and grows and grows, and

now God puts the sources of creativity participated right down into the process in human

beings so we are now new creative centers in this whole long story. Now we become created

co-creators with God of a not yet finished universe. We are a powerful new creativity that

has blossomed out in technology and all kinds of things. We have become responsible for

our own earth, and if we are not truly responsible, we can ruin our own earth. We have a

cutting edge of creativity now in this long process of the universe. It is a single great

story now, and we have this new role of being responsible for our part of the universe,

and maybe for more of it later on, and partly responsible, too, in the sense that it is in

us, as some of the scientists say, in us that the atom has become self-conscious. Only in

us does the whole unconscious material universe reach consciousness, come to the light,

and there are some who say that’s the whole purpose of it all, to come into the light

in our consciousness. We are the fulfillment of the material universe, and our role in it

then in a full vision is then to gather up the material universe into consciousness and

offer it back to God. The universe doesn’t know it is on a journey, but we do, we

can, and we should, to recognize it as a journey coming out from God, and now trying to

get back to God, and it goes out to God through us where we can offer it back to God in

recognition where it comes from, in gratitude and worship, so we can complete the story of

the material universe by gathering it up into consciousness, and we are in the middle of

it. It is part of us. The angels can’t do that. They are not part of the material

universe, but we can do it, so we have a role in the universe, a very positive role, the

new creativity in it to gather up the universe, offer it back to God, and so fulfill the

deepest longing, so to speak, or finality of the universe by bringing it into the light of

consciousness. And scientists have said, the atoms have been waiting to become conscious

in us. The highest value, the only real value is for consciousness. A totally unconscious

universe is a complete waste of time. It only has value when it comes into consciousness,

can be appreciated, and that’s our role in the universe. All of science comes in

there for us to rediscover the divine thoughts, the divine creative thoughts, rediscover

them and rethink what God first thought, and then creatively carry it on. That is a whole

positive role of man in the universe, but it requires now that you know the new science,

and learn positively from the new science. That’s a whole new phase of positive

relationship of philosophy, and philosophy of God, and theology, with science – a

positive relationship. The old fights about reductionism still have to go on, sure, but

this is a much richer, new positive picture, I think, that is very interesting.

Protestants got into it first, and a number of Anglican priests over in England who have

become philosophers and theologians. They are doing the main work, but Catholics have now

gotten into that. Fr. Christopher Mooney with his new book, Theology and the Natural

Sciences, I think it is called, is deliberately doing that. It is a fine book, so it

is a new dialogue and I think we should get into it.